Intensity of Tumor Budding as an Index for the Malignant Potential in Invasive Rectal Carcinoma

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to quantitatively assess the intensity of tumor budding in rectal carcinoma and to determine how it correlates with the malignant potential.

Materials and Methods

Intensities of the tumor budding at the invasive front of the surgical specimens from 90 patients (male, 51) with well- or moderately-differentiated rectal carcinoma were investigated. Differences in the budding intensity among pathologic variables were compared, and recurrences and survivals were analyzed in accordance with degree of the budding intensity. The patients ranged in age from 33 to 75 years (mean, 55.4) with the median follow-up being 43 months (range, 12~108).

Results

Tumor budding was identified in 89 patients (98.9%) with a mean intensity of 7.5±5.3. The budding intensity was significantly higher in tumors with lymphatic invasion (p=0.0081), blood vessel invasion (p<0.0001), and perineural invasion (p=0.0013) than in those tumor without these findings. It became significantly higher with the increase in nodal stage (p<0.0001). The intensity of tumor budding in patients with relapse (29 patients) was significantly higher than that in patients without relapse (6.2±5.0 vs. 10.2±4.9; p=0.0005), but this difference in the intensity was observed only for the node-positive patients (8.0±3.4 vs. 11.9±5.1; p=0.0064). When the patients were stratified into two groups on either side of the mean of the intensity, the higher intensity group showed a significantly less favorable disease-free (DFS) and overall survival (OS) (p=0.0026 and 0.0205, respectively). Based on the multivariate analysis, the nodal stage and the intensity of budding proved to be the independent variables associated with DFS (p=0.023 and 0.03, respectively).

Conclusion

Tumor budding at the invasive margin is a reliable pathologic index that indicates a higher malignant potential and a less favorable prognosis for patients with advanced rectal carcinoma.

INTRODUCTION

Although surgical resection remains the best curative treatment option for patients with advanced rectal carcinoma, some of the patients who have received potentially curative resection still die from their own cancers because of local, regional or distant recurrences. Until now, the standardized pathologic grading systems that only consider such parameters as mural depth and lymph node involvement of the tumor are the most widely used to predict the likelihood of long-term survival in colorectal carcinoma (CRC). Yet these systems do not reflect the biologic behavior of individual cancer tissue, which may correlate with the tumor aggressiveness and the risk of recurrence. This factor may be responsible, at least in part, for the common clinical experience where a certain group of patients appear to have a more aggressive progress of disease than others do with tumor of the same pathologic stage.

Tumor budding or sprouting refers to small clusters of undifferentiated cancer cells that are located ahead of the invasive front of the tumor, and this is a characteristic microscopic feature that represents tumor dedifferentiation, which is the first and paramount sign of tumor invasion (1,2). Its clinical significance lies in the simplicity of detecting tumor budding by use of the conventional hematoxylin-eosin (H-E) stain without further specific and/or cost-demanding techniques and superior reproducibility (3,4). Although budding has not yet been accepted as a routinely examined pathologic parameter for CRC, its relation to the prognostic significance in colon and rectal carcinoma has been evaluated in several studies (1,3~6). Provided that this simple quantitative assessment of tumor budding reflects the clinical aggressiveness of CRC cancer itself, it may complement the conventional pathologic staging systems where the biologic behavior of individual cancer tissues cannot be predicted.

The aim of this study was to evaluate if the quantitative intensity of tumor budding correlates with the clinical behavior in patients with invasive rectal carcinoma, and thus, to determine if budding quantification could help in distinguishing those patients having tumors with higher malignant potential from those patients having tumors with a lower malignant potential.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

From the database of patients who underwent potentially curative surgical resection for colorectal carcinoma under the care of the Department of Surgery, Dong-A University Medical Center from 1995 through 1999, well- or moderately-differentiated rectal carcinoma with pT2 or more were reviewed. Those patients with known familial adenomatous polyposis or cancer family syndrome, those with inflammatory bowel disease or synchronous tumors, and those who were lost to follow-up were excluded from this study. Of these, 90 patients (male, 51) were included in this study, and they ranged in age from 33 to 75 years (mean, 55.4) with the median follow-up period being 43 months (range, 12~108). The sites of relapse were diagnosed by the radiologic images (CT, ultrasonography, bone scan and/or PET scan) and/or surgical exploration, and the recurrences were classified as hematogenous (liver, lung and/or bone), nonhematogenous (locoregional relapse, systemic nodal metastases and/or peritoneal dissemination), or mixed.

The sections representing the invasive tumor margin from the specimens fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin were stained with H-E for the microscopic examinations. The histologic differentiation was based on the WHO criteria (7) and the staging was done according to Dukes classification (8), and these factors were reviewed on the routinely processed specimens. In addition, all the routine sections were carefully examined to identify venous, lymphatic and/or perineural invasion. The presence of budding was determined according to criteria proposed by Ueno et al. (4), wherein budding is defined as an isolated single cancer cell or a cluster composed of fewer than five undifferentiated cancer cells appearing to bud from a large cancer gland at the invasive front. For quantification of the tumor budding, every slide was scanned at low power magnification (×10 objective lens) to identify the areas of the highest density of tumor budding. In each tumor, three separate areas that were considered to have the highest budding density were selected and number of budding seen in each of these areas was counted using the 20-power objective lens. The tumor budding was expressed as the intensity of the tumor budding, which was defined as the highest number of tumor budding among these three areas. All the slides were interpreted for the intensity of the tumor budding by the pathologist who kept "blind" to the corresponding clinicopathologic data and patient outcomes. Fig. 1A shows a tumor with a high intensity of budding and Fig. 1B shows a tumor without budding.

Histologic findings of rectal carcinoma with abundant tumor budding (arrows; A) and without budding (B) at the invasive front (hematoxylin-eosin; original magnification, ×200).

To assess the association between the intensity of the budding and the pathologic variables, the Mann-Whitney test and Kruskal-Wallis test were used for the two group comparisons and for comparisons of more than two groups, respectively. The Mann-Whitney test and Kruskal-Wallis test were also applied to determine differences for the intensity of budding in terms of relapse and the modes of relapse, respectively. The survival curves were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method and they were analyzed by the log-rank test (9). Multivariate analyses were carried out to assess the relative prognostic value of the patients' characteristics that were associated with disease-free survival by using a Cox proportional hazard regression model (10). A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

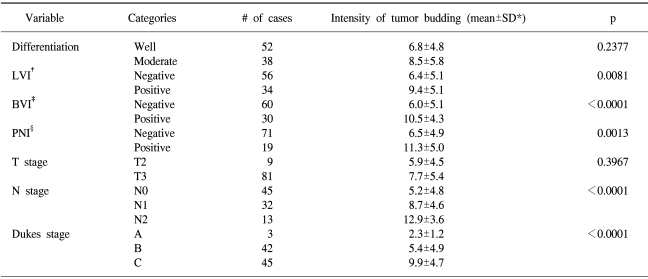

Tumor budding was identified in 89 patients (98.9%) and the mean intensity (± standard deviation) of the budding was 7.5±5.3 (median, 7). The relationship between the intensity of the budding and the pathologic variables is shown in Table 1. There were no statistically significant associations between the intensity of the budding and the histologic grade. Significant differences, however, did exist with respect to the pathologic variables, including lymphatic (p=0.0081), vascular (p<0.0001), and perineural invasion (p=0.0013). Moreover, there was a trend for the intensity to become significantly greater as the N stage, according to the AJCC/UICC classification, increased (p<0.0001), and as the Dukes stage became more advanced (p<0.0001).

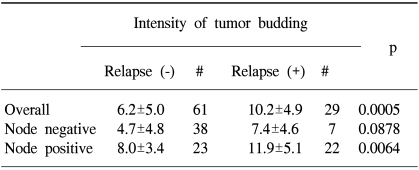

After a potentially curative resection, 29 patients (32.2%) showed relapse during their postoperative follow-up. Table 2 shows the relationship between the intensity of the budding and tumor recurrence after surgery. The intensity of the budding was significantly higher in the patients with relapse than in those patients without relapse (6.2±5.0 vs. 10.2±4.9; p=0.0005). However, when the subjects were subdivided into subgroups according to the nodal status, only the subgroup with lymph node metastasis showed a statistical significance for the budding intensity between the patients with relapse and those patients without relapse (8.0±3.4 vs. 11.9±5.1; p=0.0064). Table 3 shows the relationship between the intensity of the budding and the modes of relapse, and there was no statistical difference in the intensity of the budding according to the mode of relapse.

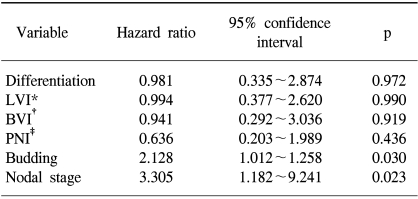

The 5-year disease-free and overall survivals (DFS and OS) for the 90 patients in this study were 67.2% and 73.9%, respectively. The subjects were stratified into the two groups that were on either side of the mean value of the budding intensity (= 7.5) and then the survival differences were compared. The 5-year DFS was 81.3% in the low-budding group (n=48), but it was only 51.3% in the high-budding group (n=42; p=0.0026; Fig. 2A). Likewise, the 5-year OS in the high-budding group was 59%, and this was significantly less favorable than the 5-year OS of 87.2% that was noted in the low-budding group (p=0.0205; Fig. 2B). On the multivariate proportional hazard model, where the routine pathologic variables and budding were considered as possible significant prognostic co-factors, the nodal stage and the intensity of the tumor budding proved to be independent variables that were associated with the postoperative DFS (p=0.023 and 0.03, respectively; Table 4).

Survival curves for 48 patients with low level of the budding and 42 with high level. Both the disease-free survival (A) and the overall survival (B) were significantly unfavorable in the high-budding group than in the low-budding group (p=0.0026 and 0.0205, respectively).

DISCUSSION

The oncologic significance of tumor budding along the invasive margin was first described by Imai (11), and he suggested that "sprouting", which corresponds to budding, represented a higher malignant potential. The term "budding" was first described in studies by Morodomi et al. (1) and more recently in studies by Hase et al. (2,12), in which they emphasized its relation to lymph node metastasis and the long-term survival. Budding is a histologic feature that appears at the invasive front of the lesion rather than at the predominant tumor site (2,12). Based on the grounds that the invasive front of the tumor has an ample blood supply (12), and that the most biologically relevant portion of the tumors with histologic heterogeneity is the area with the deepest invasion (13,14), budding in this area might reflect the biologic aggressiveness of the tumor itself.

The molecular mechanisms for the formation of budding cells have not yet been clearly defined. As tumor budding is one of the histologic features of the loss of cell-to-cell adhesion and abnormal epithelial differentiation, abnormalities of the adhesion molecules are assumed to be associated with budding (15,16). Expression of the laminin-5 γ2 chain with or without matrilysin (15,17), the laminin-5 α3 subunit in association with undefined tissue micro-environmental factors (18), or the up-regulation of the CD44 variant 6 through nuclear β-catenin activation (16) have all been suggested to contribute to the formation of budding cells at the invasive front. Further molecular researches will be necessary to clarify the precise mechanisms associated with the budding tumor cells at the invasive tumor margin.

The prerequisites for an ideal parameter to be valid are its oncologic predictability and reproducibility (19). The reproducibility of tumor budding, as measured by either the intra-observer semiquantitative agreement (4) or by the inter-observer agreement (3), proved to be almost perfect (κ value, 0.840 and 0.938, respectively). As well as the superior reproducibility of tumor budding, the technical simplicity of its identification on the routine H-E stained pathologic samples shows that determination of the tumor budding is a feasible histologic marker for representing the biologic tumor behavior. The current study clearly indicated that a higher intensity of tumor budding at the invasive front in well- or moderately-differentiated rectal carcinoma was associated with a more aggressive malignancy potential and a less favorable prognosis. Larger-scale studies are necessary to define its oncologic significance for each stage of rectal carcinoma. Tumor budding as an index of tumor aggressiveness in CRC has also been described by some investigators (2~6,12,20), and most of their results emphasized the relationship between the budding and the lymph node metastasis/lymphatic invasion (3,4,6,12). In the present study, however, strong statistical correlations were also found with the vascular invasion, and this finding was consistent with the results by Ueno et al. (4) and Okuyama et al. (20) Based on the multivariate analysis, tumor budding in this study was also proved to be an independent prognostic variable, just like was found in the other previous investigations (3,4,17,20). A recent study by Ueno et al. (21) proposed that budding is an excellent parameter to use in a grading system to provide a confident prediction of the clinical outcome.

Although the intensity of tumor budding is thought to reflect the malignant potential and the outcome for patients with rectal carcinoma, a critical bias for researchers to solve is the interpretation of this budding. Contrary to the Dukes or TNM system, where uniform parameters have been adapted for stratification, there is currently no absolute extent or level of budding intensity that definitely differentiates those patients having a more biologically aggressive tumor from those patients having a less aggressive tumor. Some studies have compared the oncologic outcome by dividing their cases into groups that were with or without budding (3,6,12,20), whereas other studies divided the groups by their own criteria (2,4,5). At least, the former classification of budding seems to be disqualified from its oncologic validity not only because the histologic features of tumor budding are quite a common phenomenon observed in 42~58% of the cases in the literature (3,6,20), and budding was seen in 98.9% of the cases in the present study, but also because the budding displays a wide spectrum of intensity in the positive cases. These are why the authors of this study assessed the significance of the intensity of budding by using absolute quantitative values, although this criterion may still be far from acceptable because of relatively large standard deviations of the intensity as related to the same pathologic or prognostic variables. These pitfalls may warrant the standardization of the interpretation to determine the high and low intensity parameters before this new interpretation of budding is routinely applied in the clinical setting.

Despite these shortcomings, the pathologic evaluation of budding might have an apparent clinical significance. Morodomi et al. (1) emphasized that budding was recognized in a relatively large portion of preoperative biopsy specimens (52 of 112; 46.4%), and lymph node metastasis was found in 41 of these 52 specimens (78.8%) as compared to 16 of 57 specimens (28.1%) in which neither lymphatic invasion nor budding was found. Moreover, Okuyama et al. (6) and Wang et al. (22) have emphasized that budding in combination with the lymphovascular invasion is a predictive marker of lymph node metastasis in curatively resected pT1 or pT2 CRC. Although the predictive significance of the budding for lymph node metastases has not been evaluated nor was it a main focus of this study, these results may illustrate what is of surgical importance for rectal carcinoma. Local excision of the rectum has been advocated for the definite treatment of selected cases of pT1 or pT2 rectal carcinomas (23). One of the most essential prerequisites for applying local excision for curative surgery in patients with rectal carcinoma is excluding those cases that have regional lymph node metastases. Endorectal ultrasound is the most widely used modality for this purpose, but its accuracy for the evaluation of regional lymph node metastases is known to be only 64~88% (24,25). From this standpoint, evaluating the intensity of tumor budding may be a useful surrogate marker to determine if an additional radical resection is indicated for the cases where the surgical specimens are not available for determining the nodal status, such as for locally excised rectal carcinomas. The definite clinical significance of tumor budding in diverse clinical settings awaits the performance of further precisely designed prospective studies.

CONCLUSIONS

Current study have shown that the intensity of tumor budding at the invasive margin, by use of a routine H-E staining, is a practical and reliable pathologic index to identify a higher malignant potential and less favorable prognosis in patients with rectal carcinoma. Further prospective studies are necessary to determine the importance of the intensity of tumor budding as a predictor for the higher risk of recurrence in rectal carcinoma.

Notes

This work was supported by the Dong-A University Research Fund in 2004.

This paper was presented at the 56th Congress of the Korean Surgical Society, Seoul, Korea, October 28-30, 2004.