MR Imaging in Endometrial Carcinoma as a Diagnostic Tool for the Prediction of Myometrial Invasion and Lymph Node Metastasis

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the factors that are associated with the accuracy of magnetic resonance (MR) imaging for predicting myometrial invasion and lymph node metastasis in women with endometrial carcinoma.

Materials and Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records and preoperative MR imaging reports of 128 women who had pathologically proven endometrial carcinoma. We compared the MR imaging and the histopathology findings.

Results

The sensitivity, specificity and accuracy for identifing any myometrial invasion (superficial or deep) were 0.81, 0.61 and 0.74, respectively; these values for deep myometrial invasion were 0.60, 0.94 and 0.86, respectively. The sensitivity, specificity and accuracy of MR imaging for detecting lymph node metastasis were 50.0%, 96.6% and 93.0%, respectively. The patients who were older, had more deliveries and a larger tumor size more frequently had incorrect prediction of deep myometrial invasion (p=0.034, p=0.044, p=0.061, respectively). A higher tumor grade, a histology other than the endometrioid type, myometrial invasion on MR findings and a larger tumor size were associated with a more frequent false-negative prediction of lymph node metastasis (p=0.018, p=0.017, p=0.002, p=0.047, respectively). A larger tumor size was also associated with more frequent false-positive results (p=0.009).

Conclusions

There are several factors that make accurate assessment of myometrial invasion or lymph node metastasis difficult with using MRI; therefore, the patients with these factors should have their MR findings cautiously interpreted.

INTRODUCTION

The estimated number of new cases of endometrial cancer and the associated deaths were reported to be 41,200 and 7,350, respectively, in the United States during 2006 (1), and the frequency of endometrial cancer is increasing in Korea. The prognosis for this malady has been directly correlated to the surgical findings, including the final tumor grade, the depth of myometrial invasion and lymph node metastases (2). In addition, the preoperative clinical and instrumental staging of local disease spread, as well as the lymph node involvement, can be a critical step for tailoring the extent of surgery (3).

Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging has proven to be an accurate tool for assessing the depth of myometrial invasion and the reported accuracies have ranged from 71% to 97% (4~5). MRI has been shown to have higher accuracy than the other imaging modalities such as sonography and computed tomography (CT) (6). MR imaging correctly differentiates the presence of deep myometrial invasion from more superficial involvement (7). MR imaging is also helpful for assessing the extent of cervical invasion (8), and for identifying enlarged pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes (9,10).

However, possible misdiagnosing the extent of endometrial carcinoma according to the MR imaging and the factors associated with this misdiagnosis have been reported by several investigators (11,12). Identifying these factors might be of great assistance to gynecologists when they are interpreting the MR imaging results. Therefore, in this study, the results of MR examinations for 128 women with endometrial carcinoma were analyzed to determine the specific factors associated with the accuracy of MR assessment for myometrial invasion and lymph node metastasis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1) Study population

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of the women who were previously treated at our hospital for endometrial carcinoma. A total of 162 consecutive patients with endometrial carcinoma were treated between 2001 and 2004. Institutional review board approval was obtained in advance for this retrospective study. The informed consent requirement was waived because of the retrospective nature of the study. The eligibility requirements for this study included: 1) histologically confirmed endometrial carcinoma by means of an endometrial biopsy, 2) and pre-operative MR imaging.

One hundred twenty-eight patients had pelvic MR imaging performed at our institute for pre-operative evaluation during the study period and they were eligible for analysis. All the patients underwent surgery, including a total abdominal hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, bilateral pelvic lymph node dissection and intraoperative washing cytology. The lymph node status was determined histologically in all the patients. The median age, the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) surgical stage and the histology of the patients are shown in Table 1.

2) MR imaging

MR imaging was performed with a 1.5 T unit (Signa; GE Medical systems, Milwaukee, WI) about 2 weeks prior to surgery. All the subjects were examined using a pelvic or TORSO multicoil. We obtained the axial T1-weighted spinecho images and the axial and sagittal fast spin-echo T2WIs. The dynamic contrast-enhanced (CE) MR images, with using gradient echo techniques, were obtained in the sagittal plane immediately and at 1, 2 and 3 min following intravenous administration of gadopentetate dimeglumine (Magnevist; Schering, Germany; 0.1~0.15 mmol/kg). The late CE T1WI was obtained in the axial and sagittal planes about 5 min after contrast administration.

3) Image analysis

Two experienced radiologists (BHK and BKP) interpreted the images prior to surgery. The radiological records were reviewed retrospectively. The criteria for interpretation followed the previously published standards (13). The depth of myometrial invasion was divided into three categories: 1) no invasion when a clear junctional zone (JZ) could be identified on a T2-weighted image and when the border between the endometrium and the myometrium was smooth and clear; 2) invasion of less than one-half of the myometrium when a partially ruptured JZ was identified or when the border between the endometrium and the myometrium was irregular, with tumor signals remaining in one-half of the myometrium, and 3) invasion of more than one-half the myometrium when a partially interrupted JZ was identified or when the border between the endometrium and myometrium was irregular, with tumor signals in more than one-half the myometrium. On MRI, lymph node metastases were diagnosed when the short-axis diameter of the LN was 10 mm or above.

4) Histopathologic analysis

Myometrial invasion was also evaluated histologically, and this was classified according to the FIGO classification as stage IA: tumor confined to the endometrium, stage IB: tumor infiltrating less than 50% of the myometrial thickness, or IC: tumor infiltrating 50% or more of the myometrial thickness. The histological results were considered as the gold standard for this study.

5) Statistical analysis

The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV), as well as the accuracy, were calculated according to standard formulae. Mann-Whitney U tests or Chi-square tests were used to determine the statistical association between incorrect MR diagnoses for myometrial invasion (or lymph node metastasis) and the clinical parameters. All the P values were two-sided, and the analyses were performed using SPSS software (Version 10.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

1) Sensitivity and specificity of MR imaging

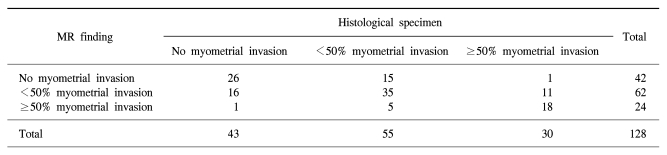

For the total series, the accuracy of predicting myometrial invasion was 61.7% (Table 2). The sensitivity, specificity and accuracy of MR imaging for detecting myometrial invasion of endometrial carcinoma were 81.2%, 60.5% and 74.2%, respectively (Table 3). The accuracy for discriminating deep myometrial invasion was 85.9%, the sensitivity was 60.0% and the specificity was 93.9%. The sensitivity, specificity and accuracy of MR imaging for detecting lymph node metastasis were 50.0%, 96.6% and 93.0%, respectively.

Depth of myometrial invasion in endometrial carcinoma: comparison of MR imaging and histological specimens

2) Variables associated with an incorrect MR determination of myometrial invasion

Table 4 shows the variables associated with an incorrect MR determination of myometrial invasion. Incorrect prediction of myometrial invasion on MR imaging occurred for 33 patients (25.8%). Among the variables we evaluated, none were associated with incorrect prediction of myometrial invasion. However, with regard to the deep myometrial invasion, the patients who were older and had a higher number of deliveries had more frequent incorrect predictions (p=0.034, p=0.044, respectively). In addition, the patients with a larger tumor size had a greater tendency for incorrect assessment of deep myometrial invasion (p=0.061).

3) Variables associated with an incorrect MR determination of lymph node metastasis

Table 5 shows the variables associated with an incorrect MR determination of lymph node metastasis. There were five cases (3.9%) of false-negative lymph node metastasis on MR imaging. A higher tumor grade, a histology other than the endometrioid type, myometrial invasion on MR findings and a larger tumor size were associated with more frequent false-negative results (p=0.018, p=0.017, p=0.002, p=0.047, respectively). A larger tumor size was also associated with more frequent false-positive prediction of lymph node metastasis (p=0.009).

DISCUSSION

Myometrial invasion in patients with endometrial cancer has been shown to be directly related to lymph node metastasis and the prognosis (14~17). Although hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy are required in most cases, conservative progesterone treatment has been reported to be an effective alternative for patients who wish to preserve their fertility (18~22). The indications for conservative treatment usually include the diagnosis of a well differentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma without myometrial invasion, and the absence of myometrial invasion has to be clinically diagnosed. MRI staging is considered the most important test among all the pretreatment examinations.

Lymphadenectomy is essential for staging endometrial carcinoma, but it can be omitted for those tumors that are limited to the endometrium because less than 1% of these patients have disease that has spread to the pelvic and/or paraaortic areas. Therefore, the pretreatment determination of lymph node metastasis is important for planning the extent of surgery. For these reasons, we assessed the reliability of MRI staging and the pitfalls associated with incorrect staging via MRI.

In this study, we found several factors associated with assessing the depth of myometrial invasion, and these included the patients' age, the number of prior deliveries and the tumor size. With regard to the prediction of lymph node metastasis, a higher tumor grade, a histology other than the endometrioid type, deep myometrial invasion on the MR findings and a large tumor size were associated with false-negative results. Therefore, the MR findings of the patients with these factors must be cautiously interpreted.

The NPV (61.9%) for the presence of myometrial invasion was low in this study (Table 3). This indicates that pathological myometrial invasion could not be excluded among the patients who were diagnosed to have no myometrial invasion by MRI. Because the signal intensity of a tiny carcinoma confined to the endometrium is similar to that of the adjacent endometrium, these two parts are indistinguishable. Previous studies have reported that the NPV varied from 28% to 100% (7,12,23,24). However, we could not determine the variables related to the incorrect prediction of myometrial invasion in this study.

A large tumor size was correlated with incorrectly predicting deep myometrial invasion, though this was statistically not significant (p=0.061). There are other previous reports that also found that the presence of large tumors may result in incorrect MR diagnoses (7). Large tumors tend to diminish the myometrial thickness and thus make it difficult to assess the degree of tumor invasion. Scoutt et al. reported that thinning of the myometrium by large polypoid tumors was significantly associated with an incorrect MR diagnosis of deep myometrial invasion (12). In addition, a large tumor size was correlated with false prediction of lymph node metastasis in this study.

The tumor histology and the depth of myometrial invasion appear to be the two most important factors for determining the risk of lymph node metastasis (2,17). Our study results showed that lymph node metastasis should not be excluded for those patients with these factors, even if there is no lymph node enlargement noted on MRI (Table 5). Therefore, full lymph node dissection should be performed in the patients with these factors, and this consistent with current clinical practice, regardless of our results.

The following limitations of our study must be acknowledged. First, this was a retrospective study that was based on radiological records; there might have been inter-observer variability. Second, most of the MR imaging was obtained after uterine curettage; some masses may have been removed during the uterine curettage or the appearance of the endometrial-myometrial interface may have been changed.

CONCLUSION

The certain characteristics such as a more advanced age, a greater number of prior deliveries and a large tumor size may make it difficult to accurately assess the depth of myometrial invasion according to MR imaging. In addition, our findings support performing full lymph node dissection in those patients who exhibit such factors such as a higher tumor grade, a histology other than the endometrioid type, deep myometrial invasion on MRI and a large tumor size.

Notes

This study was supported by a grant of the Korea Health 21 R&D Project, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (0412-CR01-0704-0001).