The Role of Radiotherapy in the Treatment of Gastric Mucosa-Associated Lymphoid Tissue Lymphoma

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

To assess radiotherapy for patients with early stage gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma with respect to survival, treatment response, and complications.

Materials and Methods

Enrolled into this study were 48 patients diagnosed with gastric MALT lymphoma from January 2000 to September 2012. Forty-one patients had low grade and seven had mixed component with high grade. Helicobacter pylori eradication was performed in 33 patients. Thirty-four patients received radiotherapy alone. Ten patients received chemotherapy before radiotherapy, and three patients underwent surgery followed by chemotherapy and radiotherapy. One patient received surgery followed by radiotherapy. All patients received radiotherapy of median dose of 30.6 Gy.

Results

The duration of follow-up ranged from 6 to 158 months (median, 48 months). Five-year overall survival and cause-specific survival rates were 90.3% and 100%. All patients treated with radiotherapy alone achieved pathologic complete remission (pCR) in 31 of the low-grade and in three of the mixed-grade patients. All patients treated with chemotherapy and/or surgery prior to radiotherapy achieved pCR except one patient who received chemotherapy before radiotherapy. During the follow-up period, three patients developed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the stomach, and one developed gastric adenocarcinoma after radiotherapy. No grade 3 or higher acute or late complications developed. One patient, who initially exhibited gastroptosis, developed mild atrophy of left kidney.

Conclusion

These findings indicate that a modest dose of radiotherapy alone can achieve a high cure rate for low-grade and even mixed-grade gastric MALT lymphoma without serious toxicity. Patients should be carefully observed after radiotherapy to screen for secondary malignancies.

Introduction

Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma is the most common hematologic malignancy, accounting for approximately 43% of all hematologic malignancies in Korea [1]. In the third nationwide study reported in 2011, extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma (MZBCL) of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) accounted for 19.0% of non-Hodgkin's lymphomas, with the second leading frequency, following diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), which represents 42.7% of cases [2]. This study reported that Korea has higher incidence rates of extranodal MZBCL compared with other Asian countries, ranging from 2.5% to 8.5% [2]. Another study of a single institution in Korea further reported that the most affected sites of extranodal MALT lymphoma are the stomach (49%), eye (36%), thyroid (4.9%), and small intestine (2.5%) [3].

Helicobacter pylori is an important causative organism for development of gastric MALT lymphoma [4], with a positive rate of approximately 90% in early stage gastric MALT lymphoma patients at diagnosis [5]. After H. pylori eradication, a remission rate of approximately 80% can be achieved in Ann Arbor stage I patients [6], but only 45% to 56% in stage II [5,7]. As may be expected, H. pylori eradication therapy alone results in a much lower response rate in patients without H. pylori infection [5]. However, the most appropriate therapeutic strategy for gastric MALT-lymphoma in patients who do not respond to H. pylori eradication or without H. pylori infection is unclear. Since randomized studies have not been performed, refractory gastric MALT lymphoma is generally treated with one or more conventional oncologic modalities, including chemotherapy, radiotherapy (RT), surgery, and more recently, immunotherapy. Unfortunately, the heterogeneity of the oncologic treatments used and the generally small sample sizes in different studies make it difficult to interpret their efficacy.

As a salvage treatment regardless of H. pylori infection status, RT is highly effective, with a superior remission rate compared to chemotherapy (97.3% vs. 85.3%, p=0.007) and surgery (97.3% vs. 92.5%, p=0.2) [7]. Given that gastric MALT lymphoma has a natural history of slow progression, remaining confined to the stomach even over several years, local field RT could be an effective treatment modality with organ preservation. However, thus far, only a few studies with small numbers of patients have reported safety and efficacy of RT for the treatment of gastric MALT lymphoma in Korea [8].

In this study, we performed a retrospective analysis to assess the role of RT as a primary or salvage treatment in patients with early stage gastric MALT lymphoma diagnosed at our institution with respect to survival, treatment response, and complications.

Materials and Methods

1. Patient enrollment

From January 2000 to September 2012, 50 patients with the diagnosis of gastric MALT lymphoma were treated with RT. Two patients lost to follow-up after RT were excluded from the evaluation. The remaining 48 patients were enrolled in this study.

2. Diagnosis and staging

All patients underwent diagnostic endoscopy and had pathologic confirmation of their diagnosis at local clinics or our institution. Although there are some differences between the cases, the main histologic features are a diffuse infiltration of lymphoid cells with lymphoepithelial lesion. The lymphoid cells showed centrocyte-like morphology, pale cytoplasm with small to medium sized, slightly irregularly shaped nuclei containing dispersed chromatin. Scattered large cells resembling centroblasts are present. Occasionally, plasma cells are also present. The lymphoid cells are immunoreactive for CD20+, CD5-, CD10-, and cyclin D1-, histologically consistent with the low-grade MALT lymphoma. Disease stage was determined based on the Ann Arbor Classification of Extranodal Lymphoma (modified by Musshoff) [6]. Work-up studies comprised patient medical history including duration and presence of local or systemic symptoms, physical examination, laboratory tests such as complete blood counts, peripheral blood smear, lactate dehydrogenase, β2-microglobulin levels, and evaluation of renal and liver function. Other staging procedures included bone marrow biopsy, chest radiographs, abdominal and pelvic computed tomography scan, and/or gastric endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS). H. pylori infection was determined by histological examination, rapid urease test, urea breath test, and/or serum anti-H. pylori immunoglobulin G antibody.

3. Treatment

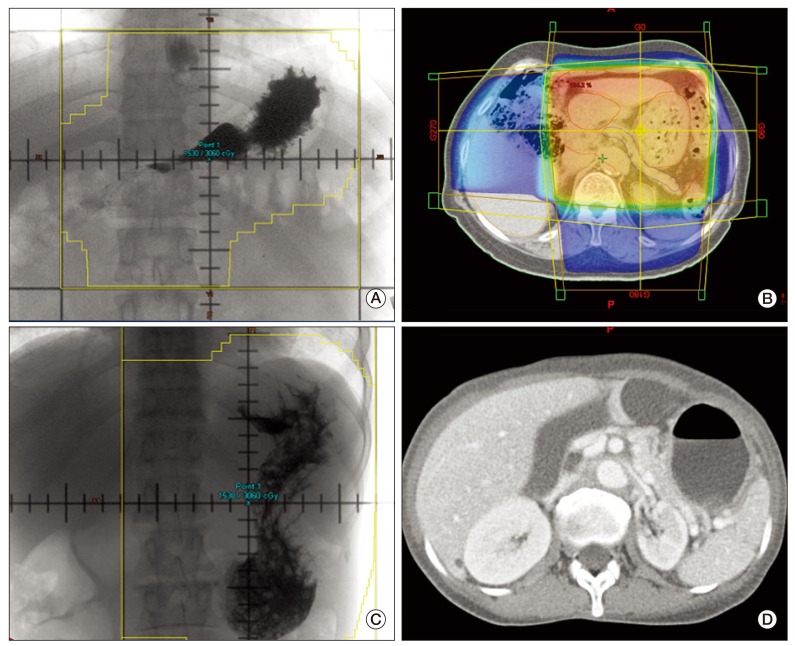

Anti-H.pylori antibiotic therapy using lansoprazole, clarithromycin, and amoxicillin was administered to 30 of 31 patients with H. pylori infection and to three of 13 patients without H. pylori infection for 7 or 14 days. Four patients without information regarding H. pylori infection status did not receive H. pylori eradication. Thirty-four of the 48 patients received RT alone. Ten patients received chemotherapy before RT with one of three regimens, including cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone (CHOP), rituximab-CHOP (R-CHOP), or fludarabine, mitoxantrone, and dexamethasone (FND). Three patients underwent surgery followed by chemotherapy and RT. One patient received surgery followed by RT. All patients received RT of median total dose of 30.6 Gy (range, 30.6 to 45.0 Gy), with a fraction size of 1.8 Gy for 3.5 to 5 weeks. Patients were treated primarily with opposed anterior and posterior two fields, or occasionally three or four fields targeting the stomach and perigastric lymph nodes with additional margins using two-dimensional (Fig. 1A) or three-dimensional conformal RT (Fig. 1B), with or without respiratory gating. All patients were treated in the supine position with an empty stomach by a 6- or 10-MV X-ray of linear accelerator on an outpatient basis.

(A) Simulation images of two-dimensional plan for radiotherapy with anterior-posterior opposing two fields including stomach and regional lymphatic area. (B) Three-dimensional plan with dose distribution shown on adjacent visceral organs. (C) Patient with gastroptosis, which required the radiotherapy field to be much larger than usual, covering entire left kidney. (D) Follow-up abdomen computed tomography showing mild atrophy with normal parenchymal density of left kidney.

4. Follow-up and statistical analysis

Response assessment was performed every three months by gastroduodenoscopy, including gathering biopsy samples, until one year after completion of RT, and every six months thereafter. Pathologic complete remission (pCR) was defined as the total disappearance of clinical evidence for lymphoma and an absence of histologic evidence for lymphoma on biopsy specimens. In cases with complete remission, endoscopic examinations and biopsies were performed at regular intervals. Blood work, including a complete blood cell count and screening profile, was performed biannually for the first two years, and thereafter annually. Chest X-ray and computed tomography (CT) scans of the abdomen and pelvis were also performed annually. The overall survival (OS), cause-specific survival (CSS), and event-free survival (EFS) rates were analyzed by Kaplan-Meier methods. OS was measured from the date of start of RT to death from any cause, and CSS was measured from the date of start of RT to the date of death due to gastric MALT lymphoma. EFS was measured from the date of start of RT to the date of death from any cause, diagnosis of relapse of MALT lymphoma or transformation to a DLBCL. Toxicity was evaluated according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE v.4.0).

Results

1. Patient clinical features

Forty-one patients were diagnosed with low-grade MALT lymphoma, and the remaining seven patients had low-grade MALT lymphoma mixed with high-grade transformation components (Table 1). Forty of these patients (83.3%) had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance score of 0. The median age of the patients was 53 years with a range of 45 to 73. Thirty-two patients (66.7%) had lesions located mainly in the mid to the lower stomach. Two patients had additional involvement of the duodenum (stage IIE2). Twenty-five patients (61.0%) had ulcerative or infiltrative endoscopic type tumors. Thirteen patients (27.1%) also exhibited intestinal metaplasia. H. pylori infection was noted in 31 patients (64.6%).

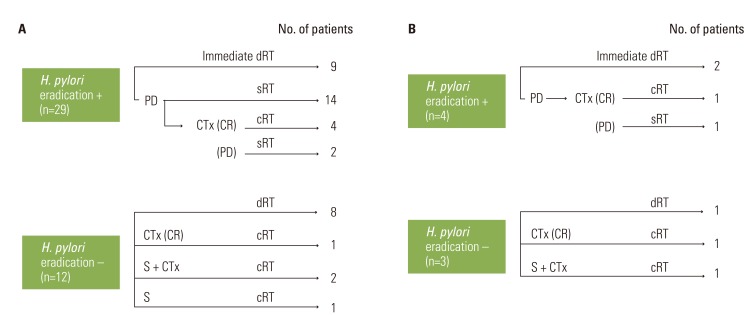

2. Treatment modality according to pathologic grade

Among the 41 patients with low-grade MALT lymphoma (Fig. 2A), 31 patients underwent RT alone. Twenty-three of these patients had H. pylori infection and underwent H. pylori eradication therapy. Of the 23 patients receiving eradication, 14 patients showed persistent disease after eradication, and the remaining nine patients underwent RT immediately after eradication without response evaluation. Another seven out of the 41 patients with low-grade MALT lymphoma underwent chemotherapy prior to RT. Of these seven, six patients showed persistent disease after H. pylori eradication, while the other patient did not undergo eradication. Of the seven patients who received chemotherapy prior to RT, five showed complete remission after chemotherapy, and two showed partial remission. Another two out of the 41 patients, who did not initially undergo H. pylori eradication, underwent a wedge resection plus chemotherapy prior to RT. One remaining patient did not undergo H. pylori eradication, but had a total gastrectomy prior to RT. Median dose of RT in these 41 low grade patients was 30.6 Gy (range, 30.6 to 43.2 Gy).

Breakdown of treatment modality by pathologic grade. Low grade (A) and low and high grade mixed (B). H., Helicoboacter; dCRT, definitive radiotherapy; PD, persistent disease; sRT, salvage radiotherapy; CTx, chemotherapy; CR, complete remission; cRT, consolidative radiotherapy; S, surgery.

Among the seven mixed grade patients (Fig. 2B), three patients had RT alone, two immediately following H. pylori eradication without response evaluation and one without H. pylori eradication. Three other mixed grade patients had chemotherapy plus RT. Two of these patients showed persistent disease after H. pylori eradication, while the other patient did not undergo eradication. Of the three patients who received chemotherapy prior to RT, two showed complete remission after chemotherapy. The other patient, who had also shown persistent tumor after initial eradication, showed partial remission. The remaining one patient with mixed grade MALT lymphoma, who also did not undergo H. pylori eradication, underwent a total gastrectomy plus chemotherapy followed by RT. The median dose of RT in these seven mixed grade patients was 37.8 Gy (range, 30.6 to 45.0 Gy)

3. Treatment outcome

The follow-up period for all patients ranged from 6 to 158 months, with a median of 48 months. The 5-year OS rate was 90.3%, CSS was 100%, and EFS was 85.2%. All thirty-four patients, 31 of low-grade and 3 of mixed-grade, treated with RT alone achieved pCR. In 10 patients who received chemotherapy prior to RT, five of seven patients with low grade and two of three patients with mixed grade achieved complete remission to chemotherapy and received consolidative involved field RT. The remaining three of 10 patients who exhibited a partial response received salvage RT, two of whom achieved a complete response. One showed a persistent tumor combined with newly developed a gastric DLBCL. The other four patients who received surgery initially, with or without chemotherapy, received consolidative RT.

Among all patients, three patients died without evidence of disease, one from renal insufficiency at 56 months, one from intracranial hemorrhage at 12 months, and one from an unknown cause at 16 months post-RT. During the follow-up period, three patients developed second malignancies (Table 2). One patient with initially low-grade lymphoma showed persistent tumor combined with DLBCL three months after chemotherapy and RT. This patient initially underwent H. pylori eradication, but had persistent disease. Following eradication, she received three cycles of FND chemotherapy, but responded only partially. The patient then received salvage RT, but showed persistent tumor mixed with DLBCL. Thereafter, the patient was salvaged completely with four cycles of R-CHOP augmented with four cycles of Rituximab and is alive without disease at 31 months after RT. The second patient had a DLBCL 38 months after completion of RT for initial low-grade MALT lymphoma. She received eight cycles of R-CHOP for newly developed DLBCL and has no evidence of disease at 64 months after RT. The third patient was diagnosed with gastric adenocarcinoma and bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (BALT) lymphoma at 44 and 51 months after completion of RT for initial low-grade MALT lymphoma. This patient had endoscopic mucosal resection for gastric adenocarcinoma (pT1 lesion), but no further treatment for BALT and expired due to renal failure at 57 months after RT. Follow-up endoscopy study for all patients after RT revealed that 13 patients had H. pylori reinfection, of whom 11 received primary or secondary eradication. Five out of these 13 patients did not have a history of H. pylori infection originally.

4. Toxicity

Acute complications were grade 2 (n=31) or grade 1 (n=1) with complaints of nausea, vomiting, dyspepsia, anorexia, diarrhea, or abdominal pain. No grade 3 or higher complications developed either as acute or late complications. Late grade 2 complications developed in three patients with gastric erosion, erythematous gastritis, and gastric ulcer. One patient, who initially had gastroptosis, developed left kidney atrophy. Because of gastroptosis, an extremely large RT field size was used to cover the entire stomach such that the entire left kidney was included within the RT field (Fig. 1C). This patient had been diagnosed with early gastric adenocarcinoma treated with endoscopic mucosal resection and BALT lymphoma (no treatment) after RT completion as described above. However, she died due to renal insufficiency with Waldenström's macroglobulinemia and metabolic acidosis at 56 months post-RT. Her kidney disease was not due to prior RT because ultrasonography of both kidneys at 52 months after RT showed mild atrophic change of the left kidney, but normal echogenicity with an intact right kidney (Fig. 1D).

Discussion

RT alone can be used to achieve complete remission for almost all low-grade gastric MALT lymphomas in cases that do not have H. pylori infection or in cases with persistent lymphoma after H. pylori eradication therapy [9-11]. A multicenter cohort study of a large number of patients with gastric MALT lymphoma reported that male gender, absence of H. pylori, location in proximal or multiple areas, non-superficial type, and advanced stage were independent predictors of resistance to H. pylori eradication therapy [5]. Among thirty-four patients treated by RT alone in our study, 25 patients received RT for the following reasons: persistent tumor after H. pylori eradication (n=14), without H. pylori eradication (n=8), and mixed grade (n=3) (Fig. 2A and B). The remaining nine patients were recommended to receive definitive RT immediately after H. pylori eradication because they had one or more factorsamong the following: submucosal or proper muscle layer involvement on EUS, diffuse gastric wall thickening or perigastric lymphadenopathy on abdominal CT. In this study, RT alone achieved pCR in all patients, including those with mixed grade, regardless of the above adverse predictors.

Gastric MALT lymphoma often is a result of H. pylori infection-associated chronic gastritis [4,12], with a positivity rate approximately 90% in early stage gastric MALT lymphoma patients at diagnosis [5]. In this study, the H. pylori infection rate was 64.6%, lower than the general infection rate, although four cases did not have information regarding H. pylori infection status. Those were likely to be H. pylori positive if a thorough examination had been done. Fourteen patients received chemotherapy and/or surgery prior to RT, due to persistent disease after H. pylori eradication or the absence of initial H. pylori eradication. Four patients in this study undertook initial surgery prior to RT, three of whom received chemotherapy postoperatively. At that time, RT was added with or without chemotherapy because these patients had surgical pathologic findings of either all layer involvement of stomach or perigastric lymph nodes metastasis. The era of performing RT on these patients was in the earlier half of this study, but later patients did not receive consolidative RT after curative surgery in gastric MALT lymphoma at our institution.

High-grade gastric lymphoma is observed in some patients at the long-term follow-up visit regardless of initial remission after H. pylori eradication [5,7]. Two patients developed DLBCL as a secondary malignancy during the follow-up period after RT. One of these patients, who had persistent MALT lymphoma after initial chemotherapy, developed DLBCL with still persistent MALT lymphoma even after salvage RT, while the other patient developed DLBCL after complete remission for MALT lymphoma after RT. These two patients were successfully salvaged by chemotherapy and were alive at the last follow-up. In a multicenter study for gastric MALT lymphoma, 8.8% of patients treated with H. pylori eradication were regarded as treatment failures, with transformation into DLBCL occurring in 24.3% of these patients [5]. Genetic aberrations such as p53 abnormalities or Bcl-6 over expression can occur in the transition from initial low-grade gastric MALT lymphomas to high-grade MALT lymphoma [12-14] or to DLBCL [15].

H. pylori infection is the strongest recognized risk factor for gastric adenocarcinoma, and much progress has been made in understanding the pathogenesis of this relationship [4,16,17]. In our study, one patient developed early gastric adenocarcinoma at 44 months and BALT lymphoma at 51 months after RT with complete remission of previous gastric MALT lymphoma. This patient did not have H. pylori infection before treatment, but was diagnosed with H. pylori infection upon follow-up endoscopy immediately after RT. There are published case reports regarding metachronous gastric MALT lymphoma and gastric adenocarcinoma [18,19]. Patients with Hodgkin's disease or non-Hodgkin's lymphomas appear to be at a higher risk of developing other cancers, and a high prevalence of secondary malignancies has been found in some gastric MALT lymphoma series [20,21]. However, there is little evidence to suggest that local RT alone is associated with an increased risk of secondary malignancies [22].

This study has two limitations. The first is that we included the seven patients diagnosed as MALT lymphoma mixed with high-grade component. World Health Organization recommended any MALT lymphoma with a partial high-grade component, whether it might be transformed from low-grade MALT lymphoma or not, should be classified as a DLBCL [23]. In the past, some pathologists have diagnosed this type as "transformation of a low-grade MALT lymphoma"or "high-grade MALT lymphoma," which might confuse a clinician in making treatment decisions. A study regarding the treatment of H.pylori positive gastric high-grade transformed MALT lymphoma reported that H. pylori eradication alone could achieve pCR rate of 64% [24]. In our study, we tried to point out that although we treated these seven patients with H. pylori eradication, RT, chemotherapy, or surgery either in combinations or alone, we could achieve pCR in three patients with mixed grade using RT alone. Further study with a larger sample is warranted to analyze the result of RT alone in mixed grade patients.

The second limitation is that some patients received consolidative RT even after achieving pCR using surgery and/or chemotherapy. Until recently, in the treatment of gastric MALT lymphoma, there was no consensus regarding standard treatment for the refractory tumor after H.pylori eradication or H. pylori negative tumor. Consolidative RT was added at that time because patients had one or more adverse predictors such as stage II or submucosal layer or deeper involvement. Now this treatment approach could be regarded as an over treatment and patients are no longer referred for consolidative RT after achieving pCR with chemotherapy or surgery in gastric MALT lymphoma at our institution.

The US National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends H. pylori eradication as a first-line treatment for H. pylori-positive gastric MALT lymphoma and RT as a second-line treatment for H. pylori-negative or refractory lymphoma [25]. However, H. pylori eradication alone does not have as high a cure rate as RT in some patients, especially with proximal or multiple tumors, non-superficial type, advanced stage, chromosomal translocation t(11;18), or mixed with high grade component [5]. Conversely, research shows that RT can achieve complete remission regardless of these adverse factors [9-11]. The current treatment protocol for low-grade gastric MALT lymphoma at our institution is that patients who have adverse predictors as above are recommended for definitive RT preceded by H. pylori eradication, if H. pylori infection is present at the initial diagnosis. However, long-term follow-up is needed to screen for the development of secondary malignancy, and if H. pylori re-infection is diagnosed, it should be re-eradicated.

Conclusion

The findings from this study show that a modest dose of RT alone as a primary or salvage treatment can achieve a high cure rate for both low- and mixed-grade gastric MALT lymphoma without serious toxicity. Careful systematic observation should be performed after RT to screen for the development of H. pylori reinfection or secondary malignancy.

Notes

Conflict of interest relevant to this article was not reported.