AbstractPurposePancreatic cancer (PC) is a common malignant tumor of the digestive system, and its 5-year survival rate is only 4%. N6-methyladenosine (m6A) RNA methylation is the most common post-transcriptional modification and dynamically regulates cancer development, while its role in PC treatment remains unclear.

Materials and MethodsWe treated PC cells with gemcitabine and quantified the overall m6A level with m6A methylation quantification. Real-time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction and Western blot analyses were used to detect expression changes of m6A regulators. We verified the m6A modification on the target genes through m6A-immunoprecipitation (IP), and further in vivo experiments and immunofluorescence (IF) assays were applied to verify regulation of gemcitabine on Wilms’ tumor 1–associated protein (WTAP) and MYC.

ResultsGemcitabine inhibited the proliferation and migration of PC cells and reduced the overall level of m6A modification. Additionally, the expression of the “writer” WTAP was significantly downregulated after gemcitabine treatment. We knocked down WTAP in cells and found target gene MYC expression was significantly downregulated, m6A-IP also confirmed the m6A modification on MYC. Our experiments showed that m6A-MYC may be recognized by the “reader” IGF2BP1. In vivo experiments revealed gemcitabine inhibited the tumorigenic ability of PC cells. IF analysis also showed that gemcitabine inhibited the expression of WTAP and MYC, which displayed a significant trend of co-expression.

IntroductionPancreatic cancer, with a 5-year survival rate of less than 5% [1], is one of the deadliest known malignant tumors. Despite major advances in detection technologies and surgical techniques, the survival and prognosis of pancreatic cancer (PC) patients are still unsatisfactory. Presently, the curative treatment for PC is still surgical resection. For patients with ineffective surgical treatment or metastases, gemcitabine is still the first-line chemotherapeutic drug for PC [2]. As the etiology for this malignant digestive system tumor has not been fully elucidated, exploration of epigenetic factors that could be novel therapeutic targets or biomarkers of PC go mainstream [3].

As a third modification recently discovered in epigenetics, RNA post-transcriptional modification regulates RNA processing, stability, and metabolism [4]. RNA modification exists in almost all living organisms, recently, an increasing number of modifications, including 5-methylcytosine (m5C), N6-methyladenosine (m6A), and N1-methyladenosine (m1A), have been uncovered, among which m6A is the most prevalent internal chemical modification [5]. m6A is mediated by the m6A methyltransferase “writers,” eliminated by demethylases “erasers,” and recognized by binding protein “readers,” thereby influencing various biological processes. m6A RNA modification in PC has been confirmed. Guo et al. [6] verified that ALKBH5 activated PER1 by m6A demethylation and led to the reactivation of ATM-CHK2-P53/CDC25C signaling, which inhibited PC progression. Insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding protein 2 (IGF2BP2) serves as a reader for m6A-modified DANCR and stabilizes DANCR RNA to promote cancer stemness-like properties and pathogenesis [7]. Additionally, METTL14 overexpression in PC promotes cells proliferation and migration through targeting the downstream p53 effector related to peripheral myelin protein 22 (PERP) mRNA in an m6A-dependent manner, thus decreasing PERP expression [8]. Additionally, methyltransferase-like 3 (METTL3) knockdown in PC cells reveals enhanced sensitivity to the anticancer reagent gemcitabine [9].

Gemcitabine is a cell cycle-specific inhibitor and is the standard first-line chemotherapeutic drug for PC patients [10]. However, whether gemcitabine has a regulatory effect on m6A modification in PC is unclear. Here, we found that gemcitabine inhibited PC cell viability and reduced the overall level of m6A modification. Mechanistically, gemcitabine decreased the “writer” WTAP (Wilms’ tumor 1–associated protein) and m6A modification on MYC mRNA, thus decreasing its expression and interfering with the activation of the downstream pathways of MYC, inhibiting PC progression.

Materials and Methods1. Collection of PC clinical information and samplesPC tissues along with adjacent normal samples were obtained from the Department of General Surgery, the First Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University. The overall experiment design and approach was approved by the Ethical Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University, and written informed consent was successively obtained from all participating patients before the study.

2. Cell cultureThe human PC cell lines PANC1 and CFPAC1 (GenePharma, Shanghai, China) were cultured with Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% antibiotics. The culture dishes were placed in an incubator at 37°C with 95% relative humidity and 5% CO2 partial pressure. The DMEM was changed every 2 days.

3. TransfectionTarget genes small interference fragment and negative control fragment (si-NC) were purchased from Synbio Technologies (Suzhou, China). Cells were evenly plated and cultured to a density of about 70% and then transfected with 50 nM siRNA using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) to downregulate the target gene expression level according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After transfection, the cells were harvested for further experiments, and all the siRNA sequences are shown in S1 Table.

4. Cell viability assayCell viability was detected with a Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) kit (Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan) according to the protocol. Approximately 5×103 PANC1 and CFPAC1 cells were seeded in 96-well plates per well after treated with or without gemcitabine for 48 hours, we checked relevant reports and conducted preliminary experiments, and finally set the gemcitabine concentration to 10 µM [11]. After incubated for 24, 48, 72, and 96hours, 10 µL CCK-8 was added and incubated at 37℃ for 2 hours, and the absorbance was detected at a wavelength of 450 nm.

5. 5-Ethynyl-2-deoxyuridineA 5-ethynyl-2-deoxyuridine (EdU) analysis kit (RiboBio, Guangzhou, China) was applied to detect the cell proliferation capability. Stable transfected PC cells were incubated with diluted 5 µM EdU reagent for 3 hours. Then, cells were permeabilized and fixed for 30 minutes, then we used Apollo and DAPI regents to stain cell DNA and nuclei. Finally, EdU- and DAPI-positive images were taken with a fluorescence microscope.

6. Transwell migration assayAfter treated with or without gemcitabine for 48 hours, appropriate 5×104 cells were evenly cultured in the upper chamber of a Transwell plate (Corning, Corning, NY) with serum-free DMEM, and 700 µL of DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum was added to the lower chamber. Then monitor cell growth status daily to ensure no apparent cells death. After normal culture for 48 hours, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with crystal violet for 20 minutes, and the cells that migrated through the upper chamber membrane were counted. Images were acquired by inverted microscopy.

7. Quantification of overall m6A RNA methylationWe used EpiQuik m6A RNA Methylation Quantification Kit (colorimetric) (Epigentek, Farmingdale, NY) to quantify the overall m6A methylation level in PC cells. First, we extracted total RNA, and approximately 200 ng RNA was separated as an initial input. Then, the sample RNA, standard positive/negative control, and binding solution were added to the wells for 1 hour for assay and capture of the RNA according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After the samples were washed, the detection antibody and enhancer solution were added, and color developer solution and stop solution were added prior to measurement of the absorbance. The values were calculated using linear regression equations.

8. RNA extraction and real-time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reactionTotal RNA was extracted from PC cells or tissues with TRIzol for quantitative analysis. RNA was first reverse transcribed to cDNA with Vazyme reverse transcriptase at 42°C for 45 minutes following the manufacturer’s protocol, and PCR was then performed using SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (GenePharma). Human ACTB was used as the housekeeping gene for mRNA expression. After 40 cycles of denaturation, annealing, and extension, the relative RNA levels were determined with the 2^-ΔΔCT method relative to the control. All the primers are listed in S1 Table.

9. Western blot analysisA radio immunoprecipitation assay lysate mixture containing 1% phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride was used to lyse and obtain total protein from PC cells. After quantification, electrophoresis was performed to separate the proteins, and then, the proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes in transfer buffer. Then, the membranes were blocked in 5% skim milk at 37°C for 1 hour and incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4℃. The next day, the membranes were incubated with an HRP-labeled secondary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature in the dark. Finally, immunoreactions were observed with a chemiluminescence detection system in a dark room.

10. WTAP and m6A immunoprecipitation assaysImmunoprecipitation assays of m6A and WTAP were performed with an RIP kit (BersinBio Biotech, Guangzhou, China). In brief, approximately 1×107 PC cells were collected and lysed for 30 minutes. DNA impurities were removed with DNase according to the protocol, and the supernatant was collected after centrifugation. The supernatant was then divided into two equal parts: one was incubated with anti-m6A or anti-WTAP primary antibodies overnight at 4℃ in a vertical orientation, and the other was used as input. Then the samples were incubated with target magnetic beads for 1 hour. After washing, RNA was extracted, and MYC expression was detected.

11. Immunofluorescence stainingTo comprehensively observe the expression relationship between WTAP and the target gene MYC, immunofluorescence staining assay was conducted. First, after deparaffinization and antigen retrieval, the sections were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and blocked with 5% BSA (Solarbio, Beijing, China). Then, the sections were stained with WTAP primary antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) and MYC primary antibody (Sigma, Darmstadt, Germany) at 4℃ overnight and incubated with the secondary antibody afterward. Finally, the cell nuclei were stained with DAPI, anti-quenching agent was added, and the sections were imaged with a confocal laser scanning microscope.

12. In vivo animal experimentTo evaluate the effect of gemcitabine on the tumor formation ability and gemcitabine/WTAP/MYC axis in vivo, we injected 2×106 PANC1 cells at logarithmic growth phase into the axilla of 4-week-old nude mice for subcutaneous tumor formation. The mice were randomly divided into phosphate buffered saline (PBS) group and gemcitabine treatment group. PBS or gemcitabine was injected into the mice via the abdominal cavity at a concentration of 50 mg/kg once every 5 days. The tumor dimension was measured every 5 days. After 30 days, the tumors were excised and weighed to compare the tumor size and volume, WTAP and MYC mRNA and protein expression was detected by real-time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) and immunofluorescence. The care of laboratory animals was in accordance with the guidelines and ethical requirements of the Laboratory Animal Centre of Soochow University.

13. Statistical analysisWe used GraphPad 8.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA) for data analysis and image generation. For statistical analysis, a two-tailed Student’s t test between two groups was performed. The Kaplan-Meier method for survival analysis. Correlational analysis of gene expression was conducted with linear regression. The scientific data are reported as the mean±standard deviation from three duplicate experiments. And the results were considered statistically significant when the p-value < 0.05.

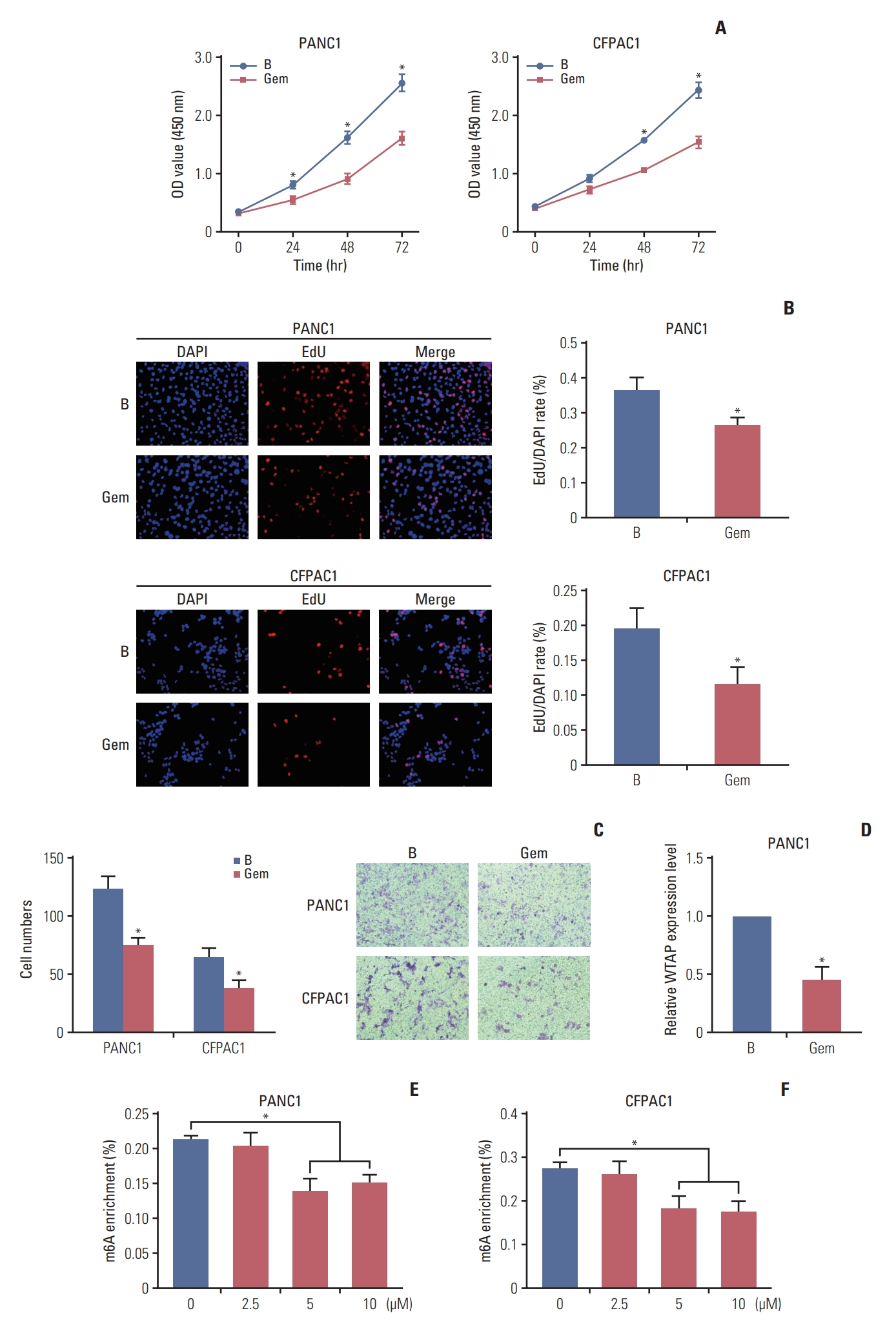

Results1. Gemcitabine inhibited PC cell proliferation and migration and decreased the overall m6A modification levelTo explore the regulatory activity of gemcitabine on m6A RNA modification, cells were treated with gemcitabine to check the cell viability changes. CCK-8 and EdU assays revealed that gemcitabine inhibited cells viability (Fig. 1A and B). Transwell assays revealed the inhibition of cell migration ability by gemcitabine (Fig. 1C), revealing that gemcitabine was an effective treatment for PC. Subsequently, m6A quantification demonstrated that gemcitabine decreased the m6A modification level (Fig. 1E and F). Considering the inhibitory effect of gemcitabine on m6A level, we wanted to explore m6A regulators that were regulated by gemcitabine. qRT-PCR demonstrated that m6A writers and erasers were changed to varying degrees by gemcitabine, among which the writer WTAP was significantly decreased (fold change=0.37, p < 0.001) (Fig. 1D), suggesting that RNA methylation might be a target for gemcitabine. TCGA analysis revealed the similar upregulation of WTAP in PC (Fig. 2A). Taken together, we took WTAP as the target of gemcitabine for further research.

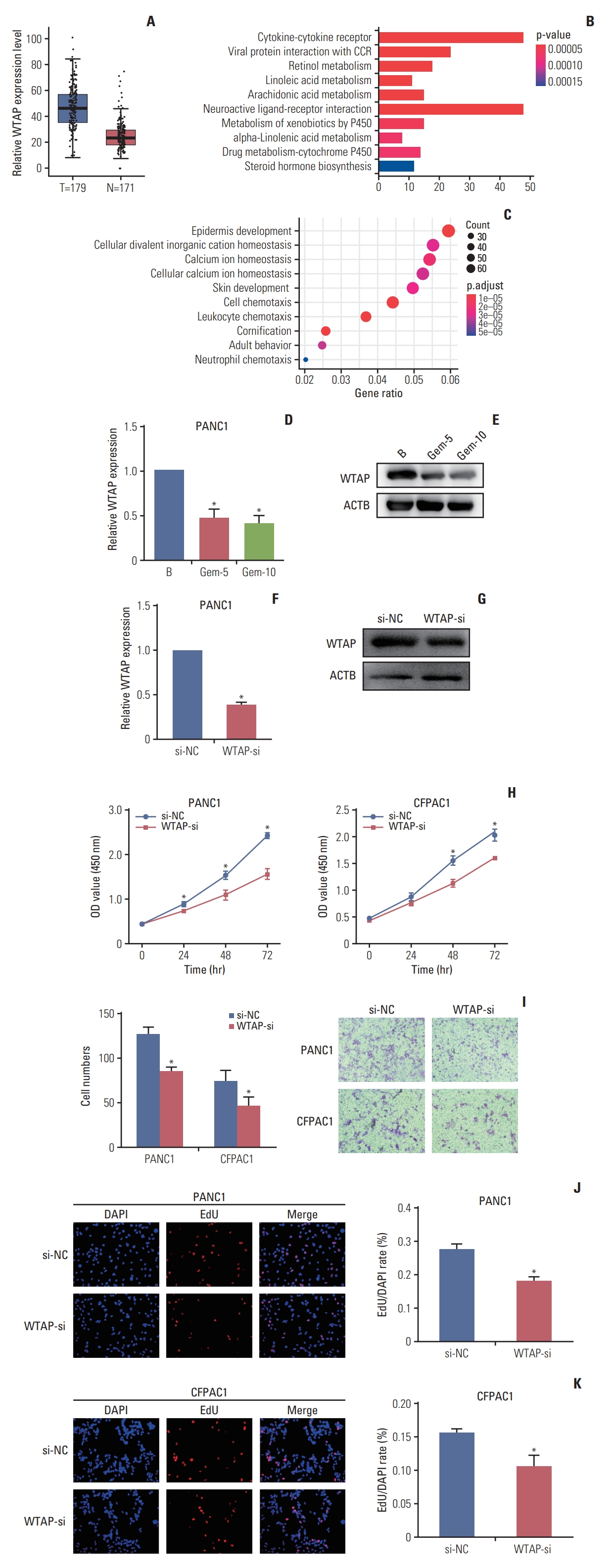

2. WTAP could be inhibited by gemcitabine and prevent PC cell proliferation and migrationAnalysis of expression pattern of WTAP revealed its high expression in PC (Fig. 2A), we then divided 173 PC specimens into WTAP high and low expression groups according to the median WTAP level, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), and gene ontology (GO) analysis revealed the important implications of WTAP on immunity and metabolism pathways (Fig. 2B and C). qRT-PCR and western blot analysis showed that WTAP expression level was reduced by gemcitabine and WTAP-si in PANC1 cells (Fig. 2D-G). CCK-8 and Transwell assays revealed that WTAP-si decreased cell viability and migration (Fig. 2H and I), which was also confirmed with EdU assays (Fig. 2J and K). Our results verified that important interaction between gemcitabine and WTAP might be significant for the clinical treatment of PC.

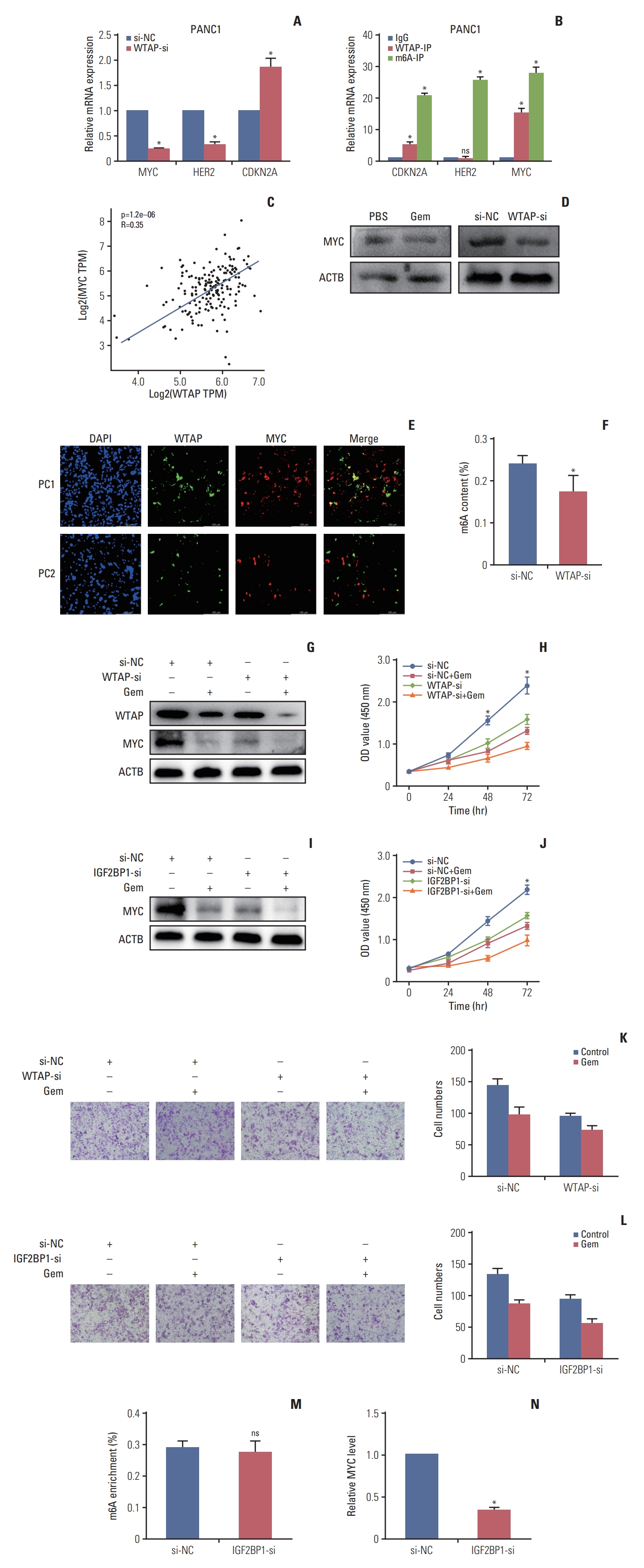

3. Gemcitabine decreased MYC stability by reducing the WTAP-dependent m6A-MYC modification levelAfter identifying the regulation of gemcitabine on WTAP, we investigated which target was regulated by gemcitabine/WTAP. We first predicted possible downstream target genes of WTAP and detected their expression changes in WTAP knockdown cells. Experimental data showed that after WTAP knockdown in PANC1, MYC, and HER2 were downregulated with fold changes of 0.25 and 0.34, respectively, while CDKN2A was upregulated (Fig. 3A). WTAP-immunoprecipitation (IP) assay showed that CDKN2A and MYC, but not HER2, were significantly enriched, suggesting that CDKN2A and MYC might be WTAP targets. Then, m6A-IP revealed that CDKN2A, HER2, and MYC were all enriched in PANC1(Fig. 3B), this lead us to speculate that CDKN2A and MYC might be methylated by WTAP but HER2 might be methylated by other m6A regulators. TCGA analysis also preliminarily verified the positive correlation between WTAP and MYC (Fig. 3C). We knocked down WTAP with siRNA in PANC1 and observed decreased MYC protein expression (Fig. 3D). Immunofluorescence analysis of PC specimens also verified the co-expression relationship between WTAP and MYC (Fig. 3E). We further experimentally verified that the level of m6A modification was also inhibited after WTAP knockdown (Fig. 3F). To give an insight into the influence of Gem and WTAP on MYC, we treated WTAP-si PANC1 cells with or without Gem to monitor MYC expression verification, we verified Gem could restrain both WTAP and MYC expression in WTAP-si cells (Fig. 3G), CCK-8 and Transwell assay verified WTAP knockdown could enhance the inhibition of Gem on cell proliferation (Fig. 3H and K).

4. IGF2BP1 recognized m6A-MYC to regulate its stability and expressionThe above results suggested that MYC is a crucial factor in PC progression. In addition, given that MYC is an indispensable proto-oncogene in various biological processes, such as metabolism [12] and the cell cycle [13], we believe that m6A-MYC is a novel treatment target in PC.

Studies found that IGF2BP1 could recognize m6A modification on MYC to alter MYC stability [14,15], so we speculated IGF2BP1 was a significant reader for m6A-MYC in PC. We found IGF2BP1 knockdown in PANC1 cells could also enhance the inhibition of Gem on MYC stability (Fig. 3I) and cell viability (Fig. 3J and L). What’s more, IGF2BP1 knockdown had no effect on m6A modification but inhibited MYC expression (Fig. 3M and N), Thus, we speculated that gemcitabine could interfere with WTAP-MYC-IGF2BP1 axis to inhibit PC progression.

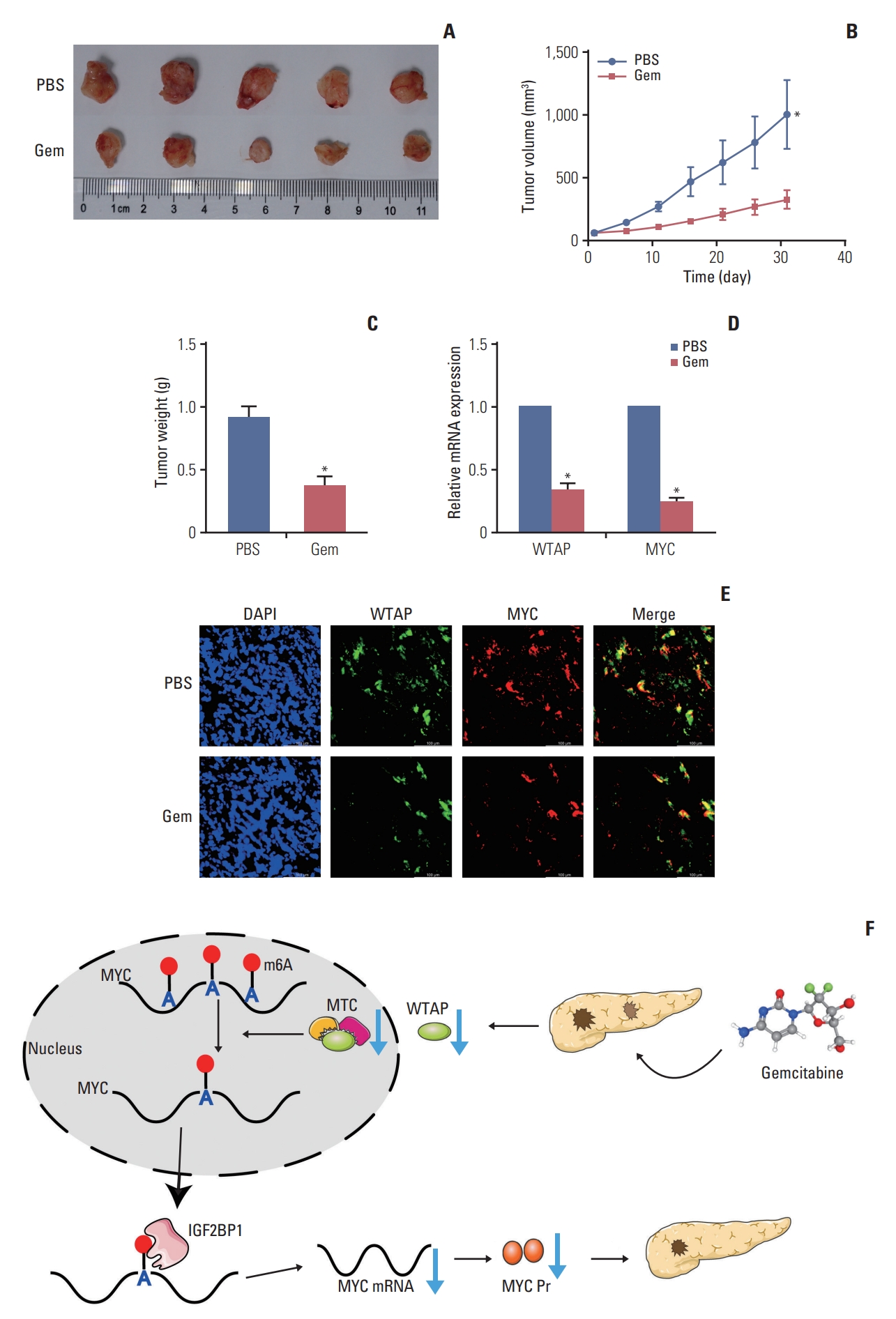

5. Gemcitabine inhibited the PC cell tumorigenic ability in vivo by reducing the expression of the WTAP/MYC axisNext, we performed in vivo experiments to further verify gemcitabine on WTAP expression and the tumorigenic ability. Gemcitabine decreased the tumor volume, central necrosis rate, and tumor weight (Fig. 4A-C), WTAP and MYC also showed a downward trend after treated with gemcitabine (Fig. 4D and E). In conclusion, our experiments showed that gemcitabine inhibits WTAP expression and reduces the m6A modification on MYC and its stability, resulting in a decrease in MYC protein expression, thereby interfering with related pathways and inhibiting the progression of PC in vivo (Fig. 4F).

DiscussionPC, with unsatisfactory 5-year survival rate, is still one of the most aggressive diseases and has a poor survival rate. Surgery remains the most effective treatment for PC, even though over 80% of patients eventually develop local recurrence or metastases [16]. Various risk factors, including environmental and inherited factors [17], epigenetic chemical modification [18], type 2 diabetes mellitus [19], and pancreatitis [20], directly or indirectly contribute to the occurrence and development of PC. As PC is characterized by a strong interstitial hyperplastic reaction around cancer cells [21], its drug resistance and early invasive metastasis indicate the need for multidisciplinary comprehensive treatment, including surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy, immunotherapy and precision medicine and targeted therapy [22].

Increasing evidence has revealed that epigenetic deregulation is critically associated with tumor occurrence and pathophysiology, of which m6A RNA methylation is the most abundant epigenetic mechanism [23]. The m6A content is critical for cancer initiation, stem cell differentiation, metabolism, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, and drug resistance [23,24]. Research has shown that METTL3 interacts with the microprocessor protein DGCR8 to modulate miR-221/222 maturation in an m6A modification-dependent manner and promote bladder cancer proliferation [25]. Additionally, METTL14 could abolish the m6A modification of lncRNA XIST and recognition by YTHDF2 and augment XIST expression [26]. Another study showed that YTHDF1 was aberrantly upregulated in ovarian cancer and regulated EIF3C translation in an m6A-dependent manner, thus affecting overall protein translation in ovarian cancer [27].

As the first-line clinical chemotherapy for PC, gemcitabine can effectively inhibit the progression of PC and prolong the survival time of patients, and the disease control rate is up to 48.4% [28]. The related mechanism of gemcitabine in the treatment of PC was initially explored, but its relationship with m6A is poorly verified. We found that gemcitabine could decrease m6A methylation level in PC cells and inhibited WTAP expression, contributed to the reduction of m6A modification on MYC mRNA. This was a major change for MYC, which eventually led to a decrease in MYC protein expression and the inhibition of downstream pathways and ultimately limited the tumorigenic ability of PC cells.

As an oncogenic transcription factor, MYC can potentially regulate approximately 15% of genomic transcription [29]. MYC can regulate major downstream processes, including ribosome biogenesis, protein translation, cell cycle, and metabolism, thereby controlling cancer biological reactions, such as cell proliferation and differentiation [30].

However, our study still has some limitations, the effect of gemcitabine on other m6A regulators needs to be investigated. The regulatory relationship between gemcitabine and MYC downstream pathways needs to be deeply discussed. Moreover, whether MYC-related genes are methylated is also an important question and worth exploring. We did not expand the sample to verify the relationship between gemcitabine and m6A in PC specimens, and we will focus on clinical specimens in subsequent experiments.

Electronic Supplementary MaterialSupplementary materials are available at Cancer Research and Treatment website (https://www.e-crt.org).

NotesEthical Statement All animal experiments were performed according to the guide for the Laboratory Animal Centre of Soochow University. The care of laboratory animals was in accordance with the guidelines and ethical requirements of the Laboratory Animal Centre of Soochow University. The overall experiment design and approach was approved by the Ethical Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University (approval number: 202110A0011), and written informed consent was successively obtained from all participating patients before the study. AcknowledgmentsThis research was supported by the Medical and Health Science and Technology Innovation Project of Suzhou (No. SKJY2021053).

Fig. 1.Gemcitabine inhibited pancreatic cancer cells proliferation and migration and overall N6-methyladenosine (m6A) modification. (A) Cell Counting Kit-8 assays were used for detection of PANC1 and CFPAC1 cells proliferation ability after treated with or without 10 µM gemcitabine (GEM). (B) 5-Ethynyl-2-deoxyuridine (EdU) assays was used for detection of PANC1 and CFPAC1 cells proliferation ability after treated with or without Gem, the ratio of EdU-positive to DAPI cells was used to represent the proliferation ability. (C) The number of cells through the transwell chamber was used to represent the migrate ability. (D) Relative m6A regulator WTAP (Wilms’ tumor 1–associated protein) expression level in PANC1 cells treated with or without Gem, ACTB was used as internal reference gene. (E, F) Relative m6A levels in PC cells after treated with or without Gem were assessed. Data are presented as mean±standard error of mean (*p < 0.05).

Fig. 2.WTAP (Wilms’ tumor 1–associated protein) was raised in pancreatic cancer (PC) and promoted PC cell biological function. (A) WTAP expression level in 179 PC specimens and 171 non-tumor specimens in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx). (B, C) Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) and gene ontology (GO) analysis of different genes between WTAP high and low expression groups in TCGA. (D, E) WTAP mRNA (D) and protein (E) expression in PANC1 cells after treated with gemcitabine (GEM), Gem-5 means PC cells were treated with Gem at the concentration of 5 µM, ACTB was used as internal reference gene. (F, G) WTAP mRNA (F) and protein (G) expression after PANC1 cells treated with WTAP-si or si-NC. (H) Proliferation ability of CFPAC1 and PANC1 cells and were detected with Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay at a wavelength of 540 nm after treated with WTAP-si or si-NC. (I) Transwell was used to detect CFPAC1 and PANC1 cells migration ability, cell numbers through the transwell chamber was counted to represent the migrate ability. (J, K) EdU assays was used for detection of PANC1 and CFPAC1 cells proliferation ability after treated with WTP-si or si-NC (*p < 0.05).

Fig. 3.WTAP (Wilms’ tumor 1–associated protein) knockdown inhibited MYC expression in a N6-methyladenosine (m6A) modification manner. (A) Relative targets RNA expression of WTAP after WTAP knockdown in PANC1, ACTB was used as internal reference gene. (B) Enrichment detection of WTAP targets by WTAP-immunoprecipitation (IP) and m6A-IP in PANC1, the results are presented as fold change of the targets in the WTAP-IP or m6A-IP experimental group. (C) Co-expression trend of WTAP and MYC in pancreatic cancer (PC) patients in The Cancer Genome Atlas. TPM, transcript per million. (D) MYC protein level in PC cells after treated with gemcitabine (Gem) or WTAP-si. (E) WTAP and MYC protein expression in two PC patient specimens by immunofluorescence. (F) Relative m6A levels in PANC1 cells after WTAP knockdown were assessed. (G-L) WTAP and insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding protein 2 (IGF2BP2) knockdown in PANC1 could enhance the inhibition of Gem on MYC expression (G, I), cell proliferation (H, J), and migration ability (K, L). (M) Relative m6A levels in PANC1 cells after IGF2BP1 knockdown. (N) MYC RNA expression change after IGF2BP1 knockdown in PANC1, ACTB was used as internal reference gene (*p < 0.05).

Fig. 4.Gemcitabine inhibited pancreatic cancer (PC) cells tumorigenesis by restraining WTAP (Wilms’ tumor 1–associated protein)/MYC axis through N6-methyladenosine (m6A) modification. (A-C) After 4 weeks of treatment with gemcitabine (Gem) or phosphate buffered saline (PBS), mice were sacrificed and subcutaneous tumors were harvested for detection and comparison of tumor volume (A, B) and weight. (D) Relative WTAP and MYC RNA expression in tumors in Gem group relative to PBS group. (E) Paraffin sections were prepared from subcutaneous tumors of mice in Gem and PBS groups, and the co-expression of WTAP and MYC protein was detected by immunofluorescence. (F) Mechanism of Gem inhibiting PC progression in an m6A modification. (*p < 0.05).

References2. Neoptolemos JP, Stocken DD, Friess H, Bassi C, Dunn JA, Hickey H, et al. A randomized trial of chemoradiotherapy and chemotherapy after resection of pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1200–10.

3. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:7–33.

4. Roundtree IA, Evans ME, Pan T, He C. Dynamic RNA modifications in gene expression regulation. Cell. 2017;169:1187–200.

5. Zhao BS, Roundtree IA, He C. Post-transcriptional gene regulation by mRNA modifications. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2017;18:31–42.

6. Guo X, Li K, Jiang W, Hu Y, Xiao W, Huang Y, et al. RNA demethylase ALKBH5 prevents pancreatic cancer progression by posttranscriptional activation of PER1 in an m6A-YTHDF2-dependent manner. Mol Cancer. 2020;19:91.

7. Hu X, Peng WX, Zhou H, Jiang J, Zhou X, Huang D, et al. IGF2BP2 regulates DANCR by serving as an N6-methyladenosine reader. Cell Death Differ. 2020;27:1782–94.

8. Wang M, Liu J, Zhao Y, He R, Xu X, Guo X, et al. Upregulation of METTL14 mediates the elevation of PERP mRNA N6 adenosine methylation promoting the growth and metastasis of pancreatic cancer. Mol Cancer. 2020;19:130.

9. Taketo K, Konno M, Asai A, Koseki J, Toratani M, Satoh T, et al. The epitranscriptome m6A writer METTL3 promotes chemo- and radioresistance in pancreatic cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2018;52:621–9.

10. Hertel LW, Boder GB, Kroin JS, Rinzel SM, Poore GA, Todd GC, et al. Evaluation of the antitumor activity of gemcitabine (2’,2’-difluoro-2’-deoxycytidine). Cancer Res. 1990;50:4417–22.

11. Xu BQ, Fu ZG, Meng Y, Wu XQ, Wu B, Xu L, et al. Gemcitabine enhances cell invasion via activating HAb18G/CD147-EGFR-pSTAT3 signaling. Oncotarget. 2016;7:62177–93.

12. Gao P, Tchernyshyov I, Chang TC, Lee YS, Kita K, Ochi T, et al. c-Myc suppression of miR-23a/b enhances mitochondrial glutaminase expression and glutamine metabolism. Nature. 2009;458:762–5.

13. Dong P, Maddali MV, Srimani JK, Thelot F, Nevins JR, Mathey-Prevot B, et al. Division of labour between Myc and G1 cyclins in cell cycle commitment and pace control. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4750.

14. Zhu S, Wang JZ, Chen D, He YT, Meng N, Chen M, et al. An oncopeptide regulates m6A recognition by the m6A reader IGF2BP1 and tumorigenesis. Nat Commun. 2020;11:1685.

15. Zhu P, He F, Hou Y, Tu G, Li Q, Jin T, et al. A novel hypoxic long noncoding RNA KB-1980E6.3 maintains breast cancer stem cell stemness via interacting with IGF2BP1 to facilitate c-Myc mRNA stability. Oncogene. 2021;40:1609–27.

16. Kleeff J, Reiser C, Hinz U, Bachmann J, Debus J, Jaeger D, et al. Surgery for recurrent pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2007;245:566–72.

17. Raimondi S, Maisonneuve P, Lowenfels AB. Epidemiology of pancreatic cancer: an overview. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;6:699–708.

18. Omura N, Goggins M. Epigenetics and epigenetic alterations in pancreatic cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2009;2:310–26.

19. Huxley R, Ansary-Moghaddam A, Berrington de Gonzalez A, Barzi F, Woodward M. Type-II diabetes and pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis of 36 studies. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:2076–83.

20. Duell EJ, Lucenteforte E, Olson SH, Bracci PM, Li D, Risch HA, et al. Pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer risk: a pooled analysis in the International Pancreatic Cancer Case-Control Consortium (PanC4). Ann Oncol. 2012;23:2964–70.

21. Ligorio M, Sil S, Malagon-Lopez J, Nieman LT, Misale S, Di Pilato M, et al. Stromal microenvironment shapes the intratumoral architecture of pancreatic cancer. Cell. 2019;178:160–75e27.

24. Zhou Z, Lv J, Yu H, Han J, Yang X, Feng D, et al. Mechanism of RNA modification N6-methyladenosine in human cancer. Mol Cancer. 2020;19:104.

25. Han J, Wang JZ, Yang X, Yu H, Zhou R, Lu HC, et al. METTL3 promote tumor proliferation of bladder cancer by accelerating pri-miR221/222 maturation in m6A-dependent manner. Mol Cancer. 2019;18:110.

26. Yang X, Zhang S, He C, Xue P, Zhang L, He Z, et al. METTL14 suppresses proliferation and metastasis of colorectal cancer by down-regulating oncogenic long non-coding RNA XIST. Mol Cancer. 2020;19:46.

27. Liu T, Wei Q, Jin J, Luo Q, Liu Y, Yang Y, et al. The m6A reader YTHDF1 promotes ovarian cancer progression via augmenting EIF3C translation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:3816–31.

28. Heinemann V, Quietzsch D, Gieseler F, Gonnermann M, Schonekas H, Rost A, et al. Randomized phase III trial of gemcitabine plus cisplatin compared with gemcitabine alone in advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3946–52.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||